[x_custom_headline type=”left” level=”h1″ looks_like=”h1″ accent=”true”]History of photography[/x_custom_headline]

[column type=”1/2″]

The history of photography commenced with the invention and development of the camera and the creation of permanent images starting with Thomas Wedgwood in 1790 and culminating in the work of the French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. Thomas Wedgwood was born in May 1771 in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England. Wedgwood is credited with a major contribution to photography and technology, for being the first man to think of and develop a method to copy visible images chemically to permanent media.

The history of photography commenced with the invention and development of the camera and the creation of permanent images starting with Thomas Wedgwood in 1790 and culminating in the work of the French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. Thomas Wedgwood was born in May 1771 in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England. Wedgwood is credited with a major contribution to photography and technology, for being the first man to think of and develop a method to copy visible images chemically to permanent media.

Sometime in the 1790s, Wedgwood devised a repeatable method of chemically staining an object’s silhouette to paper by coating the paper with silver nitrate and exposing the paper, with the object on top, to natural light, then preserving it in a dark room. The establishment of this repeatable process was, essentially, the birth of photography as we know it today.

[/column]

[column type=”1/2″ last=”true”]

Wedgwood thus became one of the earliest experimenters in photography – and certainly the earliest who deserves the title of “photographer”, conceiving of prints as pictures. It should be noted, however, that new discoveries in the prehistory of photography are being made by historians almost every year.

Photography is the result of combining several different technical discoveries. Long before the first photographs were made, Chinese philosopher Mo Ti and Greek mathematicians Aristotle and Euclid described a pinhole camera in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. In the 6th century AD, Byzantine mathematician Anthemius of Tralles used a type of camera obscura in his experiments. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) (965 in Basra – c. 1040 in Cairo) studied the camera obscura and pinhole camera, Albertus Magnus (1193/1206–80) discovered silver nitrate, and Georges Fabricius (1516–71) discovered silver chloride. Daniel Barbaro described a diaphragm in 1568. Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals (photochemical effect) in 1694.

[/column]

[clear]

[x_gap size=”50px”]

[column type=”1/2″]

The oldest surviving permanent photograph of the image formed in a camera was created in 1826 or 1827 by the French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. The photograph was produced on a polished pewter plate. The light-sensitive material was a thin coating of bitumen, a naturally occurring petroleum tar, which was dissolved in white petroleum, applied to the surface of the plate and allowed to set before use.

Exposure time in the camera was long (traditionally said to be eight hours, but possibly several days), the bitumen was sufficiently hardened in proportion to its exposure to light that the unhardened part could be removed with a solvent, leaving a positive image with the light regions represented by hardened bitumen and the dark regions by bare pewter. To see the image plainly, the plate had to be lit and viewed in such a way that the bare metal appeared dark and the bitumen relatively light.

Niépce had previously experimented with paper coated with silver chloride. Unlike earlier experimenters with silver salts, he succeeded in photographing the images formed in a small camera, producing his first results in 1816,

[/column]

[column type=”1/2″ last=”true”]

but like his predecessors he was unable to prevent the coating from darkening all over when exposed to light for viewing. As a result, he had become disenchanted with silver compounds and turned his attention to bitumen and other light-sensitive organic substances.

In partnership, Niépce (in Chalon-sur-Saône) and Louis Daguerre (in Paris) refined the bitumen process, substituting a more sensitive resin and a very different post-exposure treatment that yielded higher-quality and more easily viewed images. Exposure times in the camera, although somewhat reduced, were still measured in hours.

“Boulevard du Temple”, a daguerreotype made by Louis Daguerre in 1838, is generally accepted as the earliest photograph of people. It is a view of a busy street, but because the exposure time was at least ten minutes the moving traffic left no trace. Only the two men near the bottom left corner, one apparently having his boots polished by the other, stayed in one place long enough to be visible.

[/column]

[clear]

[x_gap size=”50px”]

[column type=”1/2″]

In 1833 Niépce died of a stroke, leaving his notes to Daguerre

More interested in silver-based processes than Niépce had been, Daguerre experimented with photographing camera images directly onto a silver-surfaced plate that had been fumed with iodine vapor, which reacted with the silver to form a coating of silver iodide. Exposure times were still impractically long. Then, by accident according to traditional accounts, Daguerre made the pivotal discovery that an invisibly faint latent image produced on such a plate by a much shorter exposure could be “developed” to full visibility by mercury fumes. This brought the required exposure time down to a few minutes under optimum conditions. A strong hot solution of common salt served to stabilize or fix the image by removing the remaining silver iodide.On 7 January 1839, Daguerre announced this first complete practical photographic process to the French Academy of Sciences, and the news quickly spread. At first, all details of the process were withheld and specimens were shown only to a trusted few.

[/column]

[column type=”1/2″ last=”true”]

Arrangements were made for the French government to buy the rights in exchange for pensions for Niépce’s son and Daguerre and then present it to the world (with the de facto exception of Great Britain) as a free gift. Complete instructions were published on 19 August 1839.

After reading early reports of Daguerre’s invention, William Henry Fox Talbot, who had succeeded in creating stabilized photographic negatives on paper in 1835, worked on perfecting his own process. In early 1839 he acquired a key improvement, an effective fixer, from John Herschel, the astronomer, who had previously shown that hyposulfite of soda (commonly called “hypo” and now known formally as sodium thiosulfate) would dissolve silver salts. News of this solvent also reached Daguerre, who quietly substituted it for his less effective hot salt water treatment.

[/column]

[clear]

[x_gap size=”50px”]

[column type=”1/2″]

In 1839, John Herschel made the first glass negative

In 1839, John Herschel made the first glass negative, but his process was difficult to reproduce. Slovene Janez Puhar invented a process for making photographs on glass in 1841; it was recognized on June 17, 1852 in Paris by the Académie Nationale Agricole, Manufacturière et Commerciale. In 1847, Nicephore Niépce’s cousin, the chemist Niépce St. Victor, published his invention of a process for making glass plates with an albumen emulsion; the Langenheim brothers of Philadelphia and John Whipple and William Breed Jones of Boston also invented workable negative-on-glass processes in the mid-1840s. In 1851 Frederick Scott Archer invented the collodion process.

[/column]

[column type=”1/2″ last=”true”]

Photographer and children’s author Lewis Carroll used this process. Herbert Bowyer Berkeley experimented with his own version of collodian emulsions after Samman introduced the idea of adding dithionite to the pyrogallol developer. Berkeley discovered that with his own addition of sulfite, to absorb the sulfur dioxide given off by the chemical dithionite in the developer, that dithionite was not required in the developing process. In 1881 he published his discovery. Berkeley’s formula contained pyrogallol, sulfite and citric acid. Ammonia was added just before use to make the formula alkaline. The new formula was sold by the Platinotype Company in London as Sulpho-Pyrogallol Developer.

[/column]

[clear]

[x_gap size=”50px”]

[column type=”1/2″]

Nineteenth-century experimentation with photographic processes

Nineteenth-century experimentation with photographic processes frequently became proprietary. The German-born, New Orleans photographer Theodore Lilienthal successfully sought legal redress in an 1881 infringement case involving his “Lambert Process” in the Eastern District of Louisiana.The daguerreotype proved popular in response to the demand for portraiture that emerged from the middle classes during the Industrial Revolution. This demand, that could not be met in volume and in cost by oil painting, added to the push for the development of photography.

[/column]

[column type=”1/2″ last=”true”]

In 1847, Count Sergei Lvovich Levitsky designed a bellows camera which significantly improved the process of focusing. This adaptation influenced the design of cameras for decades and is still found in use today in some professional cameras. While in Paris, Levitsky would become the first to introduce interchangeable decorative backgrounds in his photos, as well as the retouching of negatives to reduce or eliminate technical deficiencies. Levitsky was also the first photographer to portray a photo of a person in different poses and even in different clothes (for example, the subject plays the piano and listens to himself).

[/column]

[clear]

[x_gap size=”50px”]

[column type=”1/2″]

The new way of recording events

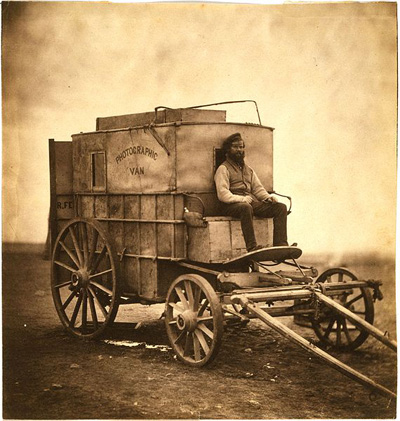

Roger Fenton and Philip Henry Delamotte helped popularize the new way of recording events, the first by his Crimean war pictures, the second by his record of the disassembly and reconstruction of The Crystal Palace in London. Other mid-nineteenth-century photographers established the medium as a more precise means than engraving or lithography of making a record of landscapes and architecture: for example, Robert Macpherson’s broad range of photographs of Rome, the interior of the Vatican, and the surrounding countryside became a sophisticated tourist’s visual record of his own travels.By 1849, images captured by Levitsky on a mission to the Caucasus were exhibited by the famous Parisian optician Chevalier at the Paris Exposition of the Second Republic as an advertisement of their lenses. These photos would receive the Exposition’s gold medal; the first time a prize of its kind had ever been awarded to a photograph.

[/column]

[column type=”1/2″ last=”true”]

That same year in 1849 in his St. Petersburg, Russia studio Levitsky would first propose the idea to artificially light subjects in a studio setting using electric lighting along with daylight. He would say of its use, “as far as I know this application of electric light has never been tried; it is something new, which will be accepted by photographers because of its simplicity and practicality”.

In 1851, at an exhibition in Paris, Levitsky would win the first ever gold medal awarded for a portrait photograph. In America, by 1851 a broadside by daguerreotypist Augustus Washington was advertising prices ranging from 50 cents to $10. However, daguerreotypes were fragile and difficult to copy. Photographers encouraged chemists to refine the process of making many copies cheaply, which eventually led them back to Talbot’s process.

[/column]

[clear]

[x_gap size=”50px”]

The modern photographic process

Ultimately, the modern photographic process came about from a series of refinements and improvements in the first 20 years. In 1884 George Eastman, of Rochester, New York, developed dry gel on paper, or film, to replace the photographic plate so that a photographer no longer needed to carry boxes of plates and toxic chemicals around.In July 1888 Eastman’s Kodak camera went on the market with the slogan “You press the button, we do the rest”. Now anyone could take a photograph and leave the complex parts of the process to others, and photography became available for the mass-market in 1901 with the introduction of the Kodak Brownie.

In the twentieth century, photography developed rapidly as a commercial service. End-user supplies of photographic equipment accounted for only about 20 percent of industry revenue. For the modern enthusiast photographer processing black and white film, little has changed since the introduction of the 35mm film Leica camera in 1925.

The first digitally scanned photograph was produced in 1957. The digital scanning process was invented by Russell A. Kirsch, a computer pioneer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. He developed the system capable of feeding a camera’s images into a computer. His first fed image was that of his son, Walden Kirsch. The photo was set at 176×176 pixels.

Roger Fenton’s assistant seated on Fenton’s photographic van, Crimea, 1855.